We’re happy to share this post from our sister site, Kids Corner @ Kindle Nation Daily, where you can find all things Kindle for kids and teens, every day!

Last week we announced that The City of Silver Light by Ruth Fox is our Kids Corner Book of the Week and the sponsor of our student reviews and of thousands of great bargains in the Kids Book category:

Now we’re back to offer a free Kids Corner excerpt, and if you aren’t among those who have downloaded this one already, you’re in for a treat!

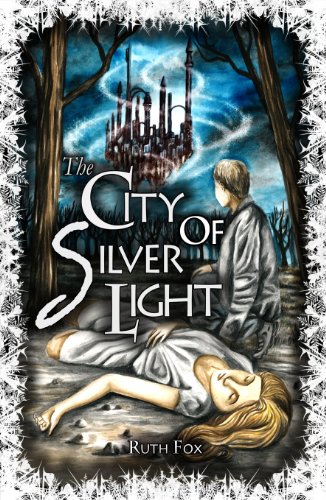

The City of Silver Light (The Bridges Trilogy)

by Ruth Fox

5.0 stars – 1 Reviews

Kindle Price: $3.49

Text-to-Speech and Lending: Enabled

Don’t have a Kindle? Get yours here.

Here’s the set-up:

On a night of frost and ice, she falls from the sky, the beautiful ice-girl Cari, cast out of her world and into ours.

It’s an unusually cold Winter, but 15 year old Jake is more concerned with the ice forming in his dad’s new relationship and the fact that the girl he likes is dating his best friend.

And now his elderly neighbour is acting even weirder than usual. Could things get even more confusing?

Then Jake finds Cari, lost and alone. Who is she? What has she got to do with the sudden frost, and the wondrous silver city that has appeared in the sky? And what does his elderly neighbour, Mrs Henders know about it all?

Jake is determined to find out. But the secrets Cari bears are more dangerous than Jake can ever imagine. And the fate of our entire world – and that of the City of Silver Light – now rest in their hands.

And here, for your reading pleasure, is our free excerpt:

Chapter One – In the Park

ON a clear night of frost and ice she falls from the sky.

I see the brilliant flash of her descent from my bedroom window. I’ve been spying on Dad, who has been sitting in the car for three hours, chain-smoking. From here I can see the entire street block, and the dark shapes of the trees in the park across the road. I can also see straight through the frost-rimmed windscreen, where Dad’s sadness glows in the streetlight.

Daniel’s small huffing exhalations are setting the rhythm of the night, but I can’t sleep when it’s like this. Too silent: a tense silence, like somebody died. I’m thinking that the ice-covered world outside might actually be warmer than inside our house, even though they’re calling this the coldest winter on record.

‘It’s global warming, Jake,’ Sharna Devon enlightened me the other morning.

The primary school Daniel goes to is down the road from Cassidy Heights Secondary College, so we catch the same bus to school on most days. My friend Keira used to save us seats but when she started going out with Andrew Dempsey she dropped that habit pretty quickly. Just like she stopped coming round to our house to muck around after school, even though she’d been doing that since we were six.

Andrew is the jealous type – and not without cause. I’ve been in love with Keira for years.

I usually try to avoid Sharna Devon, but that day the bus was full and all the other seats were taken. I tried to tune her out, drawing snowflakes on the fogged-up bus window. ‘All the climates are messed up, and the currents in the ocean are changing.’ she droned. ‘It’s the end of the world. We’ll have more earthquakes and volcano eruptions. Everyone who lives on the coast is going to get swamped when the ice caps melt.’

‘Really?’ I said, putting a finger to my chin and pursing my lips. ‘But that would be good for the fish, right?’

She gave me a disappointed look. ‘How old are you, Jake Miles?’

Later, I’d tried explaining the ozone layer and gas emissions to Daniel. My younger brother is still grappling with the idea that the world doesn’t change just because you want it to. He furrowed his brow in consternation. ‘Why don’t we just make it stop, then? If it’s such a bad thing, why don’t we fix it?’

‘If we’re ever going to stop the effects, we’d have to stop driving cars. We’d have to stop making things in factories – that means books and Play Stations and DVDs – and we’d have to stop cutting down trees to make space for houses. Because everything we’re doing just by living our everyday lives makes all this bad stuff. It’d be changing the way we live. It’d be like a different world.’

He’d pursed his lips, still confused. ‘What about Dad’s smoking?’ he said at last. ‘Is that making the hole in the ozone layer bigger?’

I told him yeah, and thought it was pretty funny when Nina yelled at him for burying Dad’s Winfield Golds in the garden in the interests of environmental conservation.

But I’m wondering now if Sharna is right and this is the beginning of the end of the world – meteor showers, comets, space-junk falling in Phoenix Park. This flash – it traces a fiery path down below the canopies of the trees. I blink the bright blue afterimage from my eyes, and though Daniel’s breathing continues uninterrupted, I know I haven’t imagined it.

I throw the blanket off my shoulders and pull on my jacket over my t-shirt. Outside it is so cold that it drenches me like water. My breath clouds the air. The world has frozen in the chill of the night, and it is beautiful. Ice clings to the shrubs by the door, and the grass glitters with jewels under the streetlights.

I pull on my runners by the door, shivering and tucking my hands in my pockets, and sprint across the lawn, which crunches under my feet. The cars parked on the road all wear shrouds of white. The shadows of the pink flamingos in number forty-seven’s front yard stretch sharply across the road. It’s silent. The world is mine alone.

I cross the road in seven steps. If anything, it seems darker under the trees of the park. The silver moonlight dapples the frozen grass. I make my way past the playground, geometric shapes against the sky, eerily still. There is a bike path winding its way through flower beds towards the lake, and I jog along this until I can see the water. Large chunks of ice float on the still surface, reflecting the moonlight. And something else – a faint orange glow. The flickering of a dying ember. I suck in a breath, amazed. It is real.

I wade through the stiff reeds towards the spot. The light of the moon gives me a crisp, clear view.

A figure lies there, curled against the spiky reeds, eyes closed, her hair tumbling over her face, wearing a white dress and covered in frost. She’s dead. She must be. Her skin is so pale, whiter than it should be even in the bleached moonlight.

The embers scattered around her hiss and crackle.

I kneel beside her and touch her shoulder. ‘Wake up,’ I say softly. School lectures about drug overdoses nag at the back of my mind.

But as I touch her, she seems to warm. Under my fingers, the frost on her dress is melting. The ice in her hair beads to water and runs in rivulets across her face, and her skin blushes with a dull pink. I stare at the transformation in wonder.

A strange feeling washes through me. I can almost feel a sudden lurching in my stomach, as if I’ve missed a step and I’m falling, but it’s cut short as her eyelids flutter and snap open. With a sudden jerk, she rears upwards and away from me, but stumbles and crashes back to the ground.

‘No!’ I call. ‘Hey! Stop –’

She cries out as I grab at her shoulder again, and I draw back. She stares at me, wide-eyed, terrified.

The cuffs and knees of my tracksuit pants are wet through now, and moisture is seeping in through the rips in my runners. I haven’t even noticed until now how cold I am, but I unbutton my jacket, forcing myself to move slowly, not to startle her. My fingers refuse to move independently, numbed by the cold, but I shrug it off and hold it out to her.

She doesn’t move, just stares at me. Those eyes! They are as blue as midnight, with the shimmering depth of water. I’ve never seen anything so unnervingly beautiful.

‘Here,’ I say, my voice constricted. ‘Put this on.’

She continues to stare.

‘I’m not going to hurt you,’ I assure her. ‘I’m a friend.’

I can’t tell if she even understands me. A full minute passes before she moves, and it isn’t to take the jacket. She leaps up and runs. I can’t move fast enough to stop her. By the time I’ve gotten to my feet she has vanished. The night is empty.

At my feet, the last of the embers flicker and die.

Chapter Two Dreams

ANGEL girl. That’s what I call her in my mind. Our family isn’t religious, but back when I was a little kid and I couldn’t sleep, Mum would tell me stories about angels. About how we each had a guardian angel, and even if we couldn’t see them, they were always there watching over us. It made me feel safe.

Later, when Daniel was born, she’d tell him the same stories and I would listen and pretend I wasn’t. ‘Sometimes,’ he’d murmured once, sleepily, ‘Sometimes when the light is right it looks like I’ve got two shadows. One of them must be my guardian angel.’

Later, when she started to get sick, Daniel, only six years old, tearfully asked why Mum’s guardian angel wasn’t looking after her.

‘She is!’ Mum had said. ‘She’s here by my side, every second of the day.’

She said this so Daniel wouldn’t worry. Me, I had a hard time imagining how much use Mum’s angel was, seeing as how she died three weeks after that, Leaving nothing but memories and empty spaces and boxes of clothes stacked in the garage.

But if there really are such things as angels, I think they would look just like this girl.

When I climb back into bed, shivering, after having shoved my soaking tracksuit pants into the laundry basket, everything seems normal. How can it be real? Girls do not actually fall from the sky in a ball of flame. It’s just a vivid dream, I tell myself.

Dad is unshaven at the breakfast table, reading the newspaper over a cup of coffee, his tie askew. Nina is bustling, a sure sign that she’s in a bad mood.

‘The water heater is on the blink again so I can’t even wash the dishes properly. I’ll have to go out and fiddle with the temperature again. Did you put your clothes out for the Salvos?’

I nod. We’ve all gotten used to Nina wanting to give things away to charity. ‘Throwing things in the bin is such a waste,’ she always says. You can’t walk with her past a council bin without having her click her tongue and mutter something about the evils of throwing away food. ‘They’re in the plastic bags in the laundry. Daniel’s, too.’

‘I was thinking I could clean out the garage today, Alex. There’s probably plenty of stuff in there the charities could use.’

Dad abruptly puts his coffee down, folds his newspaper and stands up. ‘Not today.’

‘But you can hardly get in the door,’ Nina protests. ‘Why don’t you let me neaten it up, at least?’

I make my lunch and Daniel’s, then bully him out of the door.

‘Why are you walking so fast, Jake?’ he complains. ‘The bus doesn’t come for twenty minutes!’

‘You won’t die because you missed the last few minutes of Ben Ten,’ I snap. ‘It’s like a fridge in there, anyway. I don’t want to hang around while they glare at each other behind our backs. I hate it.’

‘Do you think she’ll really clean out the garage?’ Daniel says in a small voice. I know what he’s thinking. The boxes of Mum’s clothes are in the garage. Neither of us has dared to touch them since Dad carefully taped them shut three years ago.

‘No,’ I reply. ‘Dad won’t let her.’

The cold has eased a little with the rising of the sun, but I’m wearing gloves and a beanie as well as my jacket. I’m walking fast to warm up and to put a bit of distance between myself and the house, but as we pass the park I slow down. Most of the trees are European and have lost their leaves, leaving crooked branches bare, like claws. I peer between their trunks, searching for any sign that what I saw last night was real.

‘Number forty-seven’s watching us again.’

I whirl, just in time to see the lace curtain swing back into place. The back of my neck prickles.

‘What’s Mrs Henders’ problem? Does she think we’re going to steal her horrible pink flamingos or something? What are you looking at, anyway – is there something in the park?’

‘No.’ I reply. ‘There’s nothing there.’

But even though that’s exactly what my eyes tell me, I don’t really believe it. And how can I know for sure that it’s a dream unless …

‘Walk to the bus stop by yourself,’ I say. ‘I’ve got to do something.’

‘What? What are you doing?’

‘None of your business. I’ll meet you there.’

‘Okay.’ He shrugs, already a couple of steps ahead of me. I pull out my phone and fiddle with it until he is out of sight, then glance back at our house to make sure Dad or Nina aren’t watching. Then I sprint across the road and into the park.

In the morning light things look so different. I spot two people walking along the bike path, but there is no one else around. I walk quickly across to the lake.

When I can’t see anything, I tell myself I’m an idiot for thinking I would. And that’s when my foot sinks through a piece of charred something. The area in which I stand is bare of grass, and the pieces around the edges are blackened and crushed. Around my feet are black burn-marks, partially frozen over but still visible. These marks have been left by something hot enough to melt through the ice and scorch the mud underneath.

These marks are proof that something happened last night. But what in the world could have made them – and leave behind a living, breathing girl?

And if she does exist, where is she now?

I look around. There are several pieces of flattened grass nearby, frozen in place, but that could have been done by anything in the past few days.

Right, I think. If I was as scared as angel girl was last night, where would I go? I wouldn’t want to stay around here. It’s too open. But across the lake, on the far bank, the pine plantation extends down to the shore. It is dark and thick, and I know it’s a good place to hide.

I jog the distance to keep warm, rounding the lake and ducking through the gap in the two-metre chain-link fence. The pines smell damp, and the clay of the hillside draws the temperature down another five degrees. Pine needles slip under my feet. I climb the hill, heading for a high point where I can see a wider area. Daniel and I built a treehouse here a few years ago, in the tallest pine tree, on the recommendation of Keira, who said you’d be able to see the entire area from up there; down to the park on one side and over the hill to the Garter Street bridge on the other. The treehouse is falling to pieces now; it’s just a few rotting wooden boards held in place by rusting nails.

They used to mine sandstone here and the hillside is riddled with caves and tunnels. Daniel and I know them like the back of my hand, even though we’ve been warned time and time again that such places aren’t safe. Would the angel girl have sought shelter in one of them?

I pause. Was that a noise I heard, or just my imagination? The pines creak softly. I am breathing hard from exertion, and I try to calm myself and listen. I keep climbing, but more quietly now, stopping every now and then – and I hear it again, a soft rustling of footsteps.

I don’t turn towards the sound. If she is watching me, she would be startled if I did that, and I don’t want her to run away again. So I keep climbing, then sidestep behind the thick trunk of a tree and slide back down a little way as quietly as I can. I crouch there, listening.

There is another rustling, then the sound of someone creeping towards where I last stood. I wait until they are closer … closer … slowly, I peep over the edge of the wall. A figure in a red jacket stares back at me.

‘You little shit!’ I growl, grabbing Daniel by the collar. ‘You followed me.’

‘You wouldn’t tell me what you were doing!’ Daniel protests, yanking himself free. ‘What are you doing?’

‘I’m looking for insects. It’s a science project. You’ll miss the bus!’

‘So will you,’ he reasons. ‘And why are you looking for insects here? For starters, it’s winter -’

‘It’s none of your business.’ I grind my teeth, resisting the urge to punch him. Instead I grab him by the shirt and drag him back down the hill. We miss the bus, and Nina is silent as she drives us to school.

‘You kids have a good day,’ she says as we get out of the car. She sounds like a robot.

Chapter Three Number Forty-Seven

I’M watching Keira when Baz chucks a basketball at my head. ‘Sports tryouts are on today.’ he grins as I snatch it easily out of the air. ‘Ready for the best basketball game you ever played?’

I sneer at him. ‘You reckon you even stand a chance?’

‘I’ll wipe the floor with you, Jake Miles.’

I shake my head, even though he could probably beat me if he was blindfolded, given that I can’t seem to concentrate on a single thing today.

‘So,’ Baz says, flopping down on the grass beside me and leaning in close. ‘Keira broke up with Andrew.’

We watch her. She’s playing soccer goalie with the same amount of energy she applies to everything else – far too much. She borders on hyperactive even at the worst of times. I wonder if she ever sleeps. Her pony-tail flying out behind her, she tackles the ball in midair and rolls to the ground, coming up grass-stained and yelling in triumph while Mikhal, who’d kicked what he thought would be an easy goal, shakes his head in shame.

‘Yeah,’ I say.

‘So whaddaya reckon?’

‘About what?’

‘Me and her, dickhead!’ Baz rolls his eyes.

I frown. ‘You like her?’

Baz rolls his eyes. It’s a stupid question. Everyone likes Keira. But in my estimation, no-one likes her as much as me. It’s all a complete waste of time – because she always talks to me.

Yeah, I know that should be a good thing, but the problem is that she talks to me as a friend. And that means she doesn’t even think about me in the way I think about her.

I’m not sure I like Baz thinking about her that way. Baz hardly knows her, but she used to come and play in our treehouse. She knew the plantation hideouts just as well as Daniel and I did. She had baked biscuits with my mum while I’d hovered around pinching chocolate chips. When Mum got sick, she’d come to the hospital every day with a loaf of fresh bread and a bag of fruit scones. Her mum, Mrs Leichman, worked at the local bakery.

I spin the ball on my finger. ‘You know what?’ I say. ‘I think I’ll see if I can get on the soccer team instead.’

Baz looks across at me. ‘Good idea!’ he says.

I kick myself for mentioning it.

Keira is infectious. Her energy is catching. You even breathe faster when she’s around.

‘Did you see that save?’ she says breathlessly, bouncing over to me at the edge of the oval, brushing her hair back out of her eyes. ‘I was like, I’m never going to get it, but it caught my fingers – right here on the tips – and then …’

‘I saw it,’ I say. Yeah, I saw it, right before Mr Alderston lobbed the soccer ball into my face. My nose feels like it’s broken, and has turned a shiny red. I look like a clown but Keira doesn’t even notice.

We walk back to the change rooms.

‘What are you so quiet about?’ she says, poking me in the arm hard enough to bruise. ‘Miles! Start talking!’

Talking. Again. ‘Nothing,’ I say.

‘They’re at it again, aren’t they?’

I look at her. ‘Who? What?’

‘Your dad and Nina, silly. Whatever-she-is.’

‘Yeah. I guess.’

‘So they’re fighting? Not talking? Throwing marshmallows at passing cars?’

‘Yeah,’ I say. I want to tell her more. I want to say that they smile whenever they catch me or Daniel looking at them. And that when they fight they do it in whispers, thinking that we won’t hear them. And that Dad jets off to work whenever he can, and smokes too much, and Nina pulls her lips tight over her teeth and starts tidying the house. I know Keira will understand. She cried more than I did at Mum’s funeral.

But suddenly Sharna Devon is there. They appear out of the woodwork, her friends, because they’re everywhere. Like flies. And they’re off, talking about practice, about the match next week, about talent scouts, and why Mikhal won’t ever get the ball past Keira.

***

Dad doesn’t ask me if I made the basketball team. I have to tell him I got onto the soccer team instead. His eyebrows crinkle up for a moment, because he’s forgotten that I even play sport, I think, but then he nods. ‘Oh.’ He nods again. ‘Good, good. Good.’

‘So I thought we could do some practice tonight.’

‘Yeah,’ he says. ‘Yeah, we’ll see.’

Which means he’ll be on the phone all night.

Nina cooks, and it’s pasta again. I chase the soggy stuff around my plate for a while, then say I’ve got homework to do. I pull out my maths book but keep looking out the window. I can hear the normal evening noises. Dad in the study, talking on the phone. Nina banging around in the kitchen. Daniel’s TV show. I’m unnoticed as I grab a torch and creep down the hallway and through the front door.

It’s colder than ever, like a slap across the face. I run. The lights from people’s living rooms fall over the park, but they only make deeper shadows of the trees. Number forty-seven, though, is dark. No sign ofMrs Henders.

***

I go to the lake. The patch of ash is only a dark stain under my torchlight now – could be anything really. I push through the bushes around the lake, playing the torchlight over the ground. It’s so quiet. It’s like everyone’s gone, like every living thing has suddenly disappeared, and I’m the only person left.

The stars are so bright, so sharp-edged they hurt your eyes. I’m standing on the icy grass, my head craned back to look at them, when she comes.

I don’t know where she was hiding, but when I look down she’s just there, standing in her white dress, feet bare on the frozen mud, long hair tattered and pale face stained with dirt.

‘Are you okay?’ I ask her.

She looks at me. I’m not sure if she understands. She moves her head – a nod? A shrug? I try to get a look at her eyes, to see if the pupils are dilated. I don’t think they are, but I don’t know, there are probably drugs that don’t even do that, and she must be on something because it’s not right, it’s not normal, for anyone to stand there in this weather and not be shivering.

‘What’s your name?’

She just keeps looking at me. It’s almost as if she can’t believe what she’s seeing, as if she’s trying to make sense of me. I shift uncomfortably. ‘I’m Miles. Jake, really, Jake Miles. It’s … it’s a nickname.’

She stares.

‘Aren’t you cold?’ My breath is visible in white puffs of vapour. I rub my hands together. ‘Cold? I don’t know … do you speak? Can you speak English? Ah -’ Floundering, I wonder if she’s German. We had German exchange students at school a few months ago, but they knew a bit of English, even though some of the words were all strangled. They taught us plenty of German swear words, but I’m not sure those are going to be any use right now.

What am I thinking? German? She’s not German. She fell out of the sky!

‘It’s so strange.’

It takes me a moment to realise that she has actually spoken. ‘What?’

She doesn’t answer. I wonder if she’s going to faint or something.

‘Do you know where you are?’

She says nothing. But at least I know she speaks English and she understands me. ‘You’re in Cassidy Heights. Phoenix Park. Um … that’s Mercer Street up there, towards the Garter Street Bridge, and the highway runs off Juniper Avenue. Just over the next block. Where are you from? Are you lost?’

‘I’m …’ she says softly, her voice a croak. ‘Yes. I’m lost.’

‘Right.’ I nod, trying to be confident. ‘Well, tell me where you’re from and I’ll help you get home. We live across the road. My dad’s at home, and Nina. She can drive you wherever you need to go.’

‘No.’ She shakes her head, and it’s a short, sharp shake like a convulsion. ‘No, I’m lost.’

‘I see,’ I say, not understanding at all. ‘Well, do you want to come to my house? Dad and Nina can help…’

‘No. I can’t. I have to …’ she’s looking around now, her eyes darting all over the place. ‘I have to …’

‘It’s safe. I’m not going to hurt you or anything, and it’s really cold out here. You must be freezing.’

‘No. I can’t go anywhere. I have to stay. I can’t leave.’

‘Why?’

She stares, at a loss. If she’s been out here since last night, she’ll be suffering hypothermia. Maybe it’s making her confused.

‘Look,’ I say. ‘I can’t make you do anything. But you can trust me. There’s a lot of other people around here that you probably can’t say the same for.’ I’m thinking about crazy old Mrs Henders in number forty-seven, who’s probably watching us right now. ‘If you really want to stay here, try and find somewhere warm and stay out of sight.’

If she understands, she doesn’t show it. Then a sudden noise grabs my attention – Dad, maybe, opening the front door and slipping out for a smoke – and when I turn back she’s walking away, quickly, her head down, almost running. The dark shadows swallow her up. I want to go after her, but how can I? She’d think I’m stalking her or something. And whatever is up with her is really none of my business.

I walk slowly back to the road. Number forty-seven’s lights are still off, but I catch a glimpse of movement behind the reflections on the window. A surge of anger holds me in place a moment while I glare at the vacated spot. For a moment I just want to march up and bang on the stupid old lady’s door and ask her if she doesn’t have anything better to do, but that urge is quickly quelled when the front door is wrenched unexpectedly open. I’m caught like a rabbit in the headlights.

She actually isn’t all the old, I reckon, but she has one of those faces that’s all dragged down by gravity so that her wrinkles sag under her chin, and she’s pulled her hair back so tightly it looks like a white swimming cap against her skull. Her eyes are too bright and seem to look right through you. There’s something odd about her whole appearance, but I can never work out exactly what it is.

I step away from the gate, putting my head down, ready to run for it.

‘Wait.’

It’s a command, and it’s impossible to do anything except obey. I stop and wait while she walks, moving pretty quickly, down the path between her ugly garden ornaments. All the while she’s got her eyes on me. I wonder if she even blinks. This close, I can see the fine workings of her bones beneath her skin. Her voice is soft when she finally speaks.

‘You saw, didn’t you?’

I shake my head automatically. ‘Saw what?’

‘Don’t give me that,’ she hisses. ‘You saw. I can tell.’

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about, Mrs Henders,’ I reply politely. ‘My dad’s waiting for me.’

‘Don’t tell a soul,’ she breathes. ‘No one can know. You understand that, don’t you?’

I back off. I’m already back in front of my own house as she starts to speak, jumping the fence and landing in the garden by the time she’s finished the sentence. And I’m back inside, back in my room, the words still ringing in my ears only seconds later. Daniel is pressed against the window. He looks around as I come in.

‘What did she say to you?’ he asks.

‘Nothing,’ I say, and ignore his reproachful stare. I feel weird, as if I’ve forgotten to do something important. Trying to do my homework is useless. All I can see is her, the angel girl. When I go to bed that night I feel guilty for being so warm and comfortable while she is out there – even if she doesn’t seem to mind about the cold. I wish she’d let me give her my jacket.

We go to bed but I toss and turn until Daniel rolls over. ‘Stoppit,’ he murmurs sleepily. ‘M’tryina sleep.’

I open my eyes and stare at the dim white shade of the ceiling. What was Mrs Henders on about, anyway? Had she seen the flash, too? I shiver, not at all reassured. After all, that only means that I’m just as crazy as her.

‘I can hear you,’ says Daniel, exasperated. ‘Jus’ go to sleep.’

‘Sorry,’ I say.

Chapter Four My Friend

KEIRA. If there is one thing that eclipses everything that’s tossing around in my head at the moment, it’s Keira. She’s jigging up and down in her chair, her repressed energy enough to be felt as a physical force. The science teacher has given up yelling at her.

‘You know, when it comes down to it,’ she’s saying now, ‘who really gives a crap? If Andrew’s going to go around saying all that stuff, then he’s obviously not over it, right? So he can just deal with it. It’s no one else’s problem.’

Baz is sitting next her. ‘You’re so wise, Keira. You’re like Dr Phil.’

‘Yeah.’ She rolls her eyes. ‘Coz you would know.’

‘Dr Phil? He’s my personal hero. My role model.’ He puts on a drawling accent. ‘“What the hell y’all doin’ with yer life?”’

She swats him over the head and turns to me. ‘Relationships are just so stupid. How can anyone take themselves seriously if they’re mooning around like idiots all day long? Why do you think I broke up with loser-boy?’

‘Yeah, he’s being a dick about the whole thing.’ Of course, I’ve got no idea what Andrew’s been saying about Keira, but I’m rewarded with a satisfied nod of agreement that keeps me flying through the next few minutes. That is, until Mr Jass starts handing out bits of paper and talking about a group project.

‘You’ll work in pairs,’ he says. ‘Barry, you and Miss Leichman seem to be hitting it off …’

Baz turns and pumps a fist in the air while I resignedly turn to Sharna Devon.

‘… so I’ll pair you with Sharna. Jake, you’re with Keira. See if some of your good work ethic rubs off on her, eh? Nigel, with David. Jessica …’

I give Keira a small smile that doesn’t betray my racing pulse. She grins. ‘We’ll kick their arses,’ she vows. ‘You and me, Miles. How can we lose?’ A friendly thump on the arm. ‘There’s no soccer tonight. We’ll go to your house after school.’

I’m nodding senselessly and still doing it three hours later as Keira walks with me from the bus stop. Daniel is up ahead, glancing over his shoulder at us. I ignore him.

Outside number forty seven, Keira pauses. ‘I remember we used to say she was a witch,’ she says. ‘I see her taste in garden ornaments hasn’t improved.’

I hurry her through our front gate. Maybe she didn’t see the curtain twitch, but I did, and I don’t relax until we’re inside, spreading Tim Tam crumbs all over our textbooks.

‘So basically, you want to grow some pot plants,’ she says, scrawling notes on the back of the biscuit wrapper. ‘Call it an experiment in biodiverstiy if you like, but I reckon it sounds boring as hell, Miles.’

‘Yeah.’ I have to agree. ‘But it’ll get us a pass.’

‘I don’t want to just pass. I want to blow the world away. No, I want to show Jass up. He’s a bastard.’

‘Yeah,’ I say. ‘Right.’

She sighs and leans back on the kitchen chair. ‘I hate too many people, you know. They just drive me up the wall. I need to be more like you. I need to just stand back and look. But like that thing with Andrew saying all that stuff about me at school? It gets me all worked up, and then I just get mad and everything else goes out the window.’

‘I don’t stand back and look.’ I’m not even sure what she means by that. My stupid fogged-up brain isn’t processing anything beyond the fact that a strand of her hair has come loose and is curling around her ear.

‘You do. You see things. Stuff other people always miss. You get it, see?’ She shakes her head at my uncomprehending look. ‘I can’t explain it. I shouldn’t have to. You live it every day, you should know. Just promise me you won’t go and change, right? Not like Andrew, acting like a stupid idiot all of a sudden. I need you to stay like you are forever.’

I laugh. It’s a little uncertain. ‘Um …’

‘I’m sick of this.’ Standing up, she slams her books closed. ‘But keep thinking. We need an angle on this, Miles. I don’t want to get sucked into doing just another poster with a Word Art heading. We’ll talk more later, right? Call me or something.’

When she’s gone, I find Daniel hiding on the stairs. ‘She hasn’t come round in ages. Why’s she coming round now?’ he asks.

‘We’ve got a project to do together.’

‘You should get her to fix up the treehouse. She was good at hammering nails.’

***

It’s later that night, and I’m already awake and looking out the window before I realise it. I’m looking down at the park, at an angle through the trees where I can see something moving just a little bit. It’s weird because there’s no moon out tonight, so I shouldn’t be able to see anything. It stops. It’s gone. I sit up and pull my jacket on over my tracksuit.

Into the night. I walk across the road, into the shelter of the trees. Just there, under one of the oaks, she’s standing and staring up at the sky. One hand is flat against the bark as if to hold her steady. ‘They’re gone,’ she says softly. She shakes her head, a lost, hopeless gesture.

‘Can I help?’

‘I don’t think so,’ she says. ‘No. I’m pretty sure you can’t. Why do you keep coming back?’

I hesitate. ‘I saw you fall the other night. I saw the flash.’

Her eyes are shadowed and I can’t tell what she’s thinking.

‘I’m not going to tell anyone,’ I blabber. ‘I meant what I said. You can trust me. If you don’t want anyone to know you’re here, I won’t tell them, but you can’t just stay here. Sooner or later … well, it’s not safe.’

‘It’s never safe.’ Her voice is really quiet now, barely audible. ‘Not here.’

‘What did you mean?’

She sighs. ‘I don’t think you’d understand.’

‘You did fall. I saw it happen.’

I want her to deny it. I want her to laugh and say that’s stupid, and only crazy old ladies like Mrs Henders make up stories like that.

She doesn’t.

‘And things like that don’t happen every day. At least, not that I know of. How could I not come back?’

She regards me through the veil of shadows.

‘You don’t have to tell me anything. Just let me get you some food and a blanket. Please.’

A silence, longer this time, as she turns her gaze back to the sky. She does speak, but not for a while. ‘I was talking about the stars. The stars are gone.’

‘It’s only clouds,’ I assure her. ‘The stars are still there, you just can’t see them.’

‘I really, really wish I could see them.’

I stare at her. ‘Look, I can’t stay out here all night. My brother will wake up and notice I’m gone. If you want me to bring you some food, well, I will. Or clothes or anything. Just let me know.’

‘I am hungry,’ she says slowly.

Grinning, I offer my hand, then hastily withdraw it when I realise what I’m doing. ‘Come with me,’ I say instead.

And she does.

Chapter Five The Gift

AT night, spaces are warped. Everything looks different. I turn the light on in the kitchen, but it doesn’t chase away the strange sense of being awake while the rest of the world is asleep. I pull out a chair and she sits down tentatively – she moves like a cat, warily looking around, tensed and ready to spring for the door. Her eyes are wide as she takes in the fridge, the bench covered in dishes, the microwave, the rubbish bin. She looks like she’s never seen anything like them.

‘There’s not much to choose from,’ I say, pulling a bottle of juice out of the fridge, and some leftover pizza. I pour the juice into a glass, and she looks at the pizza cautiously.

‘It smells bad,’ she says.

I frown. ‘It’s fine. We ordered it for tea. Only a couple of hours ago.’

‘No.’ She shakes her head. ‘It smells of dead things.’

‘It’s got ham on it.’

‘Is that something that died?’

‘Yeah, I guess. Ham used to be pigs.’ Her expression stops my laughter. It’s as if I just told her that she’d have to eat vomit. ‘Are you vegetarian?’

‘I don’t know what that is.’ She’s perplexed.

‘Well, there’s not much else – um, oh, there’s this. Garlic bread. Daniel hates it so there’s tons left.’ I pull off the foil and put it in the microwave. The girl watches carefully as it lights up and the plate starts to revolve.

The microwave beeps, and I pull the plate out and set it in front of her. She falls on it, tearing off a bit and cramming it in her mouth. It’s painful to watch. ‘It tastes …’ she frowns.

‘You don’t like it?’

‘No. It’s good.’

As if to prove it, she devours the rest in under a minute. I pour her some more juice, and manage to find a can of peaches, which she inhales as well. I wouldn’t have thought it the most appetising combination, but she doesn’t complain.

‘I’ve always wondered about these wrappers. All the food here comes packaged and labelled,’ she says, toying with the empty can.

‘Well, yeah. The packaging makes it last longer. And helps you pick which brand you want.’

‘Thank you for the meal,’ she replies politely.

‘Don’t go back to the park,’ I plead. ‘We’ve got a garage. No one ever goes in there. It’s only full of boxes of …’ I pause, thinking about exactly what the garage is full of – the cardboard boxes that Dad taped shut so carefully, as if by sealing them tightly enough, he could keep his memories of Mum inside them, safe for years to come. ‘Well, full of old stuff.’

She shakes her head. She won’t stay. ‘I need to be in the park,’ she says. ‘Just in case.’

‘Well, at least I can give you something warm to wear.’ I go through the door into the laundry. Thank goodness for Nina’s charitable urges – the bags we filled for the Salvo’s winter appeal are in the corner. I pick out one of Daniel’s old jackets and a thick woollen blanket. ‘You can take these with you.’

She nods her head. ‘Thank you.’

‘Be careful. Don’t let anyone see you.’

The door is closed, and she is gone into the swirling ice-mist of early morning.

Back in bed, I barely sleep at all. When Nina gets Daniel up, she wakes me as well, but she’s working and leaves early. I fall back to sleep, only to wake up at eight-thirty and realise I’ve got ten minutes to shower, get dressed, pack my bag and get to the bus stop.

I’m walking bleary-eyed past number forty-seven when Mrs Henders looms up in front of me.

‘You be careful,’ she croaks.

‘I’m really late,’ I say, moving to step past her. Quick as a flash, she grabs my arm, her bony fingers digging in like sharp claws.

‘You’ve got to be careful,’ she says, and she shoves something at me.

‘What is this?’

She smirks. ‘Something I made. Something you’ll need.’

Suddenly the hand is gone, and she’s shambling back up the path as if nothing happened. I’m left holding the whatever-it-is. It’s wrapped in brown felt. Slowly, carefully, I let it unfold in my hands. Inside is a tube of dark metal – it looks like brass, which explains the weight. It’s an old fashioned telescope, tarnished with age.

What the hell?

I turn it over in my hands, shaking my head. And then I remember I’m late for the bus, and I shove it into my pocket and sprint like hell.

***

‘Hey Miles!’ Baz grabs me from behind in a strangle-hold. I shake him off. In my pocket, the telescope shifts, and I grab it to make sure it doesn’t fall out.

‘What?’

‘You missed soccer last night.’

I realise it’s true. I’d completely forgotten about practice.

‘You missed the action,’ he goes on.

‘What?’

‘What do you think?’ At my blank look, he sighs impatiently. ‘Where’s your head today? I’m talking about Keira, numbnuts!’

‘What about her?’

He rolls his eyes. ‘She was practically begging me to ask her out, yesterday.’

‘She said relationships were for idiots.’

‘She’s going out with me!’

Ice-crystals form in my veins. I can feel them pricking my heart. ‘She’s going out with you.’

He’s already bouncing down the hallway.

I get through homeroom, maths, and history, but when it comes to recess I’m ready to collapse. I want to crawl back into bed and pretend that this day never happened.

Baz is playing no-rules footy with some of the other guys in the hallway, bouncing the ball off light-fittings and people’s heads, and I can’t even look at him without feeling like I’m going to throw up, so I grab my jacket and sit outside near the library and pretend to eat my lunch. It tastes like crap so I end up just sitting there, and when Keira plonks herself down next to me, I jump.

‘What’s up?’

I’m about ready to throw up again. ‘Nothin’.’

‘Bull.’

She can say whatever she wants, but I’m not talking.

‘You up for the movies on Friday? That new one – The Witch.’

I shrug. It’s all about some gruesome murder, which really suits my mood right now, but honestly …

‘Well, we’re all going.’

‘Baz too?’ It just slips out, and she kind of stiffens up. Not that I’m watching, I’m too busy studying the remains of my salad roll spread out on my lap.

‘Yeah,’ she says. ‘Yeah, I guess you heard.’ She’s smiling a little bit, at the corners of her mouth. ‘You know, I never reckoned he would ask me out, but he walked me home from soccer practice and he was so sweet.’

‘Right.’ Really, I don’t want to hear it.

‘And yeah. It’s a good thing. Right?’

‘What you said, yesterday, when you were talking about Andrew,’ I remind her.

‘I only said people who act like him should be shot. Baz isn’t like that. It’s good. It’s like we’re still best mates.’

I feel things shift around in my stomach. Ugh. ‘I think I want to work on our project on Friday.’

‘Really?’ She sounds really surprised. ‘Well, okay, Miles. Don’t expect me to hang with you, though. I’m busting to go out, so I’ll let you do the homework-obsessed loner thing, okay?’

‘No worries,’ I say. ‘See you.’

I’m in such a bad mood I wag the last two periods and walk home. But when I reach my house I don’t go inside. I cross the road into the park.

Sitting on the bench by the pond, I take out the telescope. The metal is so cold it burns me. I rub my fingers over the worn surface, but it doesn’t warm up with my body heat.

Crazy Mrs Henders. Why, out of all the people she probably spies on, does she have to pick on me to talk to?

I pull out the extendable sections. They’re stiff and I have to twist them to get them to move. The eyepiece is ice-cold when I put it to my eye. The view it shows me is nothing remarkable – the glass is smudged and scarred with scratches. I can see the faint shapes of two joggers. Strangely, they’re both surrounded by a shifting turquoise cloud. The trees on the far side of the pond look blurred and out-of-focus, and they’re all surrounded by a faint red haze.

It’s weird. They don’t look any closer, but there’s a definite rose tinge clinging to the trunks and branches. When I move the telescope higher, the haze turns to a soft orange. I guess the glass must be tinted or have filters or something in it that have discoloured over time.

When I shift the telescope to the side a little, I catch sight of a thin yellow line. It stops short of touching the tops of the trees. At first I think it’s a vapour trail from an aeroplane, but it’s too thin and straight.

I lift the telescope, tracing the line upwards. But the sky that should have been there … isn’t there.

This fact registers calmly in my mind, as if someone had just told me that their favourite band was Good Charlotte. I’m looking up at what should have been the clouds, but I’m seeing clear blue sky instead, shot through with bright little pinprick stars. The yellow streak reaches up and vanishes. Right there, hanging before my eyes, it’s … it’s unimaginable. Spires and turrets, the tallest towers stretching up impossibly high. Bridges span the distances between them, tiny slender things like strands of a spider’s web. In the light of late evening, against the backdrop of stars, it shines silver. It’s a city. It’s a city in the sky.

It’s a city.

Slowly, very slowly, I remove the telescope from my eye. The clouds are back. There is nothing, not a trace to show how this could have happened, how this illusion could have been performed. I shake the telescope. Almost reluctantly, I replace it against my eye. The city shimmers into being.

I am insane.

Suddenly not wanting to touch the thing anymore, I tuck the telescope into my backpack. I’m only sitting there for about three minutes before she shows up, walking across the grass. She looks odd, holding a folded blanket and wearing Daniel’s old jacket over her white dress, but though it doesn’t really disguise the strangeness about her I’m glad that she looks less … remarkable.

‘You look pale,’ she says.

She looks really concerned, and for a moment I’m just going to sit here and lap it up. People should be concerned! For a moment I get the urge to tell her everything, about Keira and Baz, about Mrs Henders, about what I just saw in the sky. She won’t laugh. She won’t call me insane. She’ll listen carefully and nod and look at me with those deep blue eyes.

But I don’t. I don’t want to talk about any of it. Grasping for normality I give her the answer I would give Dad or Nina – a shrug. ‘I’m fine. Just school stuff.’

‘Oh,’ she says.

‘But what about you? Are you warmer?’

‘Yes. I’ve never been cold, ever, before I came here. But this place is so different. I can’t quite work things out.’ She shakes her head. ‘You’re purple,’ she says, and then shakes her head, frustrated, when she sees I’m confused. ‘Upset, and sad. I’m curious – school is a place you go to learn about history and writing?’

I give a little snort, because I think she’s joking. But she’s not. She just looks at me and I have to tell her. ‘School is pretty much about everything but learning. How can you not know about school?’ Where in the world is there a place that kids don’t go to school? Is she from Africa or some third world country? Surely not with that pale skin … I’m doing it again. She’s not from Africa, or Germany, I tell myself. Angel girl is not from here at all.

‘I do,’ she says. ‘I know some things. I’ve watched it sometimes.’

‘That doesn’t make any sense.’ I sigh. ‘I said I wouldn’t ask you questions, so I won’t ask where you’re from again. But I’d really like to know.’

She smiles slightly. ‘Did you do badly? In one of your history or writing lessons?’

‘No.’ I’m short with her this time. I’m respecting her privacy, even though it’s killing me. Why can’t she do me the same courtesy? ‘I’ll get you some food. Oh, wait. Come with me. Nina will be home, but that doesn’t matter.’

She looks wary. ‘I’m not all that hungry.’

‘You have to eat,’ I tell her. ‘Come on. Nina’s probably done some shopping.’

We walk out of the park. I glance at number forty-seven. Even though there’s no movement behind the curtains, I reckon she’s watching us. I feel the weight of the telescope in my pocket – I’ll have to hide it somewhere later, so that Daniel doesn’t find it. I feel like I’ve got a million secrets!

‘You’re early,’ says Nina. She’s in the kitchen, bills spread out on the table in front of her, and she looks up when we come in. She looks a bit startled to see us. I wonder if she’ll recognise Daniel’s old jacket, but she doesn’t seem to notice. ‘Oh. Hello.’

‘This is Rebecca,’ I cover quickly. ‘From my class. We’re doing homework.’

‘Hi, Rebecca. I’m Nina.’

Oh, I hate that so much, that suck-up ‘I’m the coolest adult ever’ look she gets on her face every time she meets one of our friends. I grit my teeth and bear it. I don’t want to start arguing with her.

‘Do you want Milo? There’s some biscuits in the cupboard. Or bread – there’s jam, or Nutella.’

‘Thanks,’ I say. I’m already getting out the milk and mugs.

‘Are you working on the science project too?’ Nina asks.

I get a panicked look.

‘No. She’s in a different group. They’re doing animal migration patterns.’ To tell you the truth, I’m a bit surprised at how easily all these lies are coming out.

‘Well, if you need any help with that, one of my friends works for the EPA – she could probably give you some pretty good information …’

‘Thanks, but we’re all supposed to do the research ourselves.’

I’m not waiting for milk to warm up – I chuck the Milo in cold, grab some biscuits and lead the way out from under Nina’s eager gaze.

In the bedroom, she sits on the edge of Daniel’s bed like she’s going to get up and bolt at a moment’s notice. She takes a tentative sip of Milo and her eyes light up. ‘It tastes wonderful. Like spices and sweetness.’

I raise my eyebrows.

‘This is where you sleep?’ she goes on, her eyes roving over the room.

‘Yes. That’s my brother’s bed.’

She nods. ‘You have a brother?’

‘Yeah. He’s a pain.’

‘You don’t like him?’

‘Does anyone like their siblings?’ I shake my head. ‘He’s not too bad, as brothers go. He’s a lot like me though, and I don’t know – I don’t know if that’s a good thing.’ I want to ask her if she’s got any brothers or sisters, but I promised I wouldn’t pry. But in the next instant, she’s answered my question for me.

‘I’d like it,’ she says. ‘I think I would. If I had a brother. I’ve seen brothers and sisters together here. I’d like to have someone I was that close to.’

It’s the most she’s ever said at one time. I’m kind of shocked. ‘Well, if you want to take him, go ahead.’

A moment, just a moment, and I think I can see the faintest trace of a smile on her lips. It takes hold tentatively, like she’s used to laughing out aloud but hasn’t done it in a very long time. ‘What’s his name?’

‘Daniel.’ I finish my Milo. ‘And I’m Jake. Jake Miles. Remember, I told you?’

She nods. ‘I remember you, Jake Miles.’

For a moment I think she’s going to tell me her own name, but no such luck – she seems to realise what she’s doing and she’s sitting up straight again, her eyes darting around. I can almost see her folding in on herself.

‘That’s Nina, who you met in the kitchen. And my dad – Alex – he’s at work. He always is.’

‘Does he like being at work?’

‘I don’t know. I don’t think so. I think he just likes not being here.’

‘I would like to work,’ she says. ‘If I could.’

‘Work at what?’ And why? Work doesn’t seem particularly appealing to me. Look at how it makes Dad act, the way he gets all cut up about things, and comes home silent, and locks himself in his study for hours without talking to anyone and if one of us makes a noise he’ll come out and yell like anything. And Nina, well, her job doing part-time accounting just sounds boring. ‘You don’t go to school, right? So you’ve got plenty of free time. Why can’t you work?’

‘It’s … hard to explain. Things are very different where I come from. When I was little, I always wanted to be a … a healer.’

I frown. ‘Like a doctor.’

She brightens a moment. ‘Yes! A doctor. It’s all I wanted to do.’

‘So why don’t you? You can get a casual job and save up, then go to uni …’ even as I speak the words, I know I’m saying the wrong thing. Casual job. Uni. They’re words that she doesn’t know, concepts that don’t apply to her.

‘Here, that is what you would do. But in my place it is very different. People have their roles to fulfil and choice does not come into it. And now …’ Here she pauses for a long moment, her face going oddly still. I might be imagining that there are tears in her eyes, but I see her lower lip quiver.

‘Now?’

‘I don’t know.’ Her voice lowers to a whisper. ‘I don’t even know if I can ever go home.’

‘Don’t cry,’ I say, embarrassed because she says this with such sadness that I think it’s going to make me start bawling.

‘I’m not,’ she says it as if she truly believes that she’s not. She puts her empty cup on the floor and stands up, moving towards the door, making her escape.

‘No -’ I start after her. I really don’t want her to leave, not now, when she’s actually talking to me and I’m close to discovering who she is. I can’t let her. I grab her arm to stop her, and in that instant I’m –

I’m –

I am.

I’m here, I’m not, I’m nothing compared to the everything I’ve become. Suddenly I am part of the wind outside the window, the noise of the TV in the lounge room, the minute vibrations of the house as wood and brick and plaster shifts infinitesimally. I can see at once Daniel’s Ben Ten poster on the wall and Nina downstairs, still sitting at the table and staring blankly at the bills spread out in front of her, and a jogger in the park and a bird flying towards a red rooftop and my own hand gripping her arm. But not only this, I feel them – the crispness of the paper and the rush of air against feathered wings and the thud of the earth beneath the joggers feet and the echoing click of Nina’s fingernails on the Laminex.

I can’t think of any other way to describe it. It’s like it’s all there – no, it’s always been there, but now I realise how much a part of it I am, and how much everything is a part of everything else. It’s all linked, from the tiniest molecule of air to the sound of traffic on the distant highway, from the smell of Milo to the feel of her ice cold skin under my fingers. I let go, and with a jolt, I am dumped back into my body. Her arm falls to her side and she looks at me and I see in her midnight eyes horror and fear. She backs away from me. ‘You shouldn’t have done that.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I apologise uselessly, dizzy from the shock of it all. I put my hand against the wall to feel something solid because the world is rocking. It’s just like that first time I touched her, in the park, just after she fell – but it’s a thousand times worse. I feel like I’m going to throw up.

She turns, and bolts down the hall. I can’t go after her. I kneel down and put my forehead on the floor, the carpet pressing deep into my skin, which feels suddenly too hot, too tight. I kind of scrunch myself up into a little ball of pathetic human flesh, a waste of space, a waste of energy and breath.

‘Are you okay?’

It’s Daniel, Daniel’s voice, but it’s like a tonne of rocks falling down a mountainside, a piece of sandpaper being forced through my eardrum. I moan, hoping he’ll understand, somehow, but of course he’s chewing on a muesli bar – I can hear his teeth grinding away at the little grains, splitting them open – and he’s full of after-school energy. ‘Who’s that?’

I roll out of the doorway, prop myself against the wall, and push the heel of my hand into my temple as if that will help.

‘Jake? Jake? Who was that?’

‘No one,’ I mutter.

‘What’s wrong with you? You look sick. Who was that girl? She was wearing my jacket.’

‘You gave that jacket away to the Salvo’s.’ I’m not really listening to what I’m saying. ‘It’s not yours anymore.’

He purses his lips, takes another slow, noisy bite of his muesli bar and crinkles the wrapper up in his hands. ‘Why doesn’t she have her own clothes?’

‘Because some people just don’t,’ I return. ‘Which is why you gave away your jacket in the first place. And you can’t choose who gets stuff you throw away. That’s just stupid.’

‘You’re stupid!’ he retorts. ‘You look really sick. I’ll get Nina.’

‘No!’ I yell. He jumps a bit. I’m startled by the way that comes out, too. ‘No, I don’t want her to know, Daniel. I just got a headache. I’ll be fine in a bit. I already feel better.’

It’s true. Things are fading, falling back into place. My ears are still ringing, but the sounds have diminished. I still feel nauseous, but I think I can choke it down. I tuck the telescope under my pillow and by tea-time, I’m feeling normal enough to snap at Nina when she goes on about the girl.

‘Rebecca seems nice,’ she says. ‘A bit quiet.’

I shrug, knowing that she’s comparing her to my other friends. To Baz. And Keira. Of course, I know what she’s thinking. That I’m being a moody teenager and going through ‘a stage’, or whatever adults call it when you’re younger than they are and they don’t understand you. I don’t know why, because honestly, the way she and Dad carry on, you’d think they were the ones going through a stage.

‘She doesn’t look like a Rebecca,’ says Daniel.

I glare at him.

‘She doesn’t! It doesn’t suit her.’

Nina intervenes. ‘You should have told her to stay for tea.’

‘She had to get home.’

‘Well, you should invite her around some other time, then. We’ll have lamb or something. A roast.’

I think about the angel girl’s reaction to pizza. ‘She’s vegetarian. Is Dad going to be late?’

‘He’s always late,’ says Daniel.

‘About eleven. Don’t wait up for him – he went in at four this morning so he’ll probably just go straight to bed. You know.’

Yeah. I know. I guess asking him to help me work on my soccer kicks is out of the question, again.

‘And anyway, you could use an early night, I think, Jake. You look a bit peaky.’

For once, I accede, allowing her to bully me into bed with another cup of Milo, hot this time. As the steam curls up past my face, she sits down on the edge of the bed. ‘He’s just busy, you know. It’s hard work.’

‘Everything’s hard work.’

‘But it’s harder for some people.’ She sighs. ‘Look, don’t worry about it, okay? He’s up for a promotion soon. A higher pay rate means he’ll be able to spend less time at the office.’

‘Or even more.’

She frowns. ‘Don’t speak like that. If you had any idea …’

‘Sorry,’ I mumble.

She sighs. ‘No you’re not. I remember what it was like. I was fifteen too, and my parents were never around. I was selfish and I hated them because there were all these things happening in my own life that were difficult, and then I felt guilty for hating them because I never would have talked to them about it anyway.’

I wonder if I’m supposed to feel sorry for her. I don’t. I’m too tired.

‘I’m not saying life is more complicated when you’re an adult than when you’re a kid, but the problems are proportional, you know? And they affect more people because there’s a hell of a lot more responsibility involved. I know it’s hard being fifteen, but it’s not easy being forty-one either.’

She pats at my bedcover, stands up. ‘Good night, Jake.’

I don’t answer her. The Milo tastes far too sweet and the heat of it burns the roof of my mouth.

Later, I turn over in my sleep. Before I even know I’m doing it, I grab the telescope from beside my pillow, where it’s wedged against the wall. I sit up and, taking a deep breath, I look through the window.

It’s there, that strange glowing rope trailing up to the sky. The city is brighter now in the darkness. It glitters. I crouch down so that I can see more of it.

The sight of it makes me gasp. My eyes, still sore from the evening’s assault on my senses, hurt to see something so bright. I see the towers, the bridges, the beautiful splendour of it all. It’s magnificent.

I suddenly wonder about Mrs Henders. Where did she get the telescope from? There’s only one reason why she would give it to me. She knows about the city.

Click here to buy the book: The City of Silver Light by Ruth Fox>>>